INSIDE THIS EDITION:

- Spring Convocation Keynote Address: ART, WHAT IS IT GOOD FOR? SOME THOUGHTS ON FIRST PRINCIPLES by Tony Estrella, Artistic Director, Gamm Theater

- From the Winter/Spring 2024 Memoir Class: TINY MEMOIR by Naomi Appel; THE DA DA CHING TRUCK by Jeanne Medeiros

- AIR: "a breath on the line" – A show by LLC member Liliana Fijman at the Sprout Gallery, Providence (Apr 9-May 3)

- THE CHATBOTS ARE COMING by Robert Kemp

Click on the links to jump to the article.

Spring Convocation Keynote Address:

Art, What Is It Good For? Some Thoughts on First Principles

TONY ESTRELLA

Artistic Director at The Gamm Theater for 20 seasons

Since his first show with the company, Antony & Cleopatra, he has appeared in or directed more than 70 productions. His favorite roles include Frank in Brian Friel’s Faith Healer, George in It’s a Wonderful Life: A Live Radio Play, Shannon in The Night of the Iguana, Hamlet in Hamlet, Moe Axelrod in Awake and Sing!, Valere in La Bete, Katurian in The Pillowman, Teach in American Buffalo, and Vanya in Uncle Vanya.

Since his first show with the company, Antony & Cleopatra, he has appeared in or directed more than 70 productions. His favorite roles include Frank in Brian Friel’s Faith Healer, George in It’s a Wonderful Life: A Live Radio Play, Shannon in The Night of the Iguana, Hamlet in Hamlet, Moe Axelrod in Awake and Sing!, Valere in La Bete, Katurian in The Pillowman, Teach in American Buffalo, and Vanya in Uncle Vanya.

Directorial highlights include Hangmen, Bad Jews, Describe the Night, Assassins, JQA, True West, Festen, Sara Kane’s 4:48 Psychosis, A Streetcar Named Desire, Red, and the U.S. premieres of Howard Brenton’s Paul and Sarah Waters’ The Night Watch. Tony has written several works for The Gamm stage including A Lie Agreed Upon (2021), and adaptations of Dylan Thomas’ A Child’s Christmas in Wales, Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House and Hedda Gabler, and Barry Unsworth’s acclaimed novel Morality Play.

In addition to The Gamm, he has appeared on numerous regional stages. He most recently appeared in Joshua Harmon’s A Prayer for the French Republic at The Huntington Theatre in Boston. His film credits include appearances in Martin Scorsese’s The Departed, Kenneth Lonergan’s Manchester by the Sea, Greta Gerwig’s Little Women, and The Good House. He is a recipient of the Claiborne Pell Award for Excellence in the Arts and is a longtime member of the theater faculty at his alma mater, URI.

“We can’t live longer, but we can live deeper.”

From the Memoir Class Winter/Spring 2024

Tiny Memoir

by Naomi Appel

When I was 14 and he was 15, I would find notes in my locker that said “Marry me, Sara, how happy we will be – little you and big old me.” I didn’t need a name to know who it was. He was one year older and one foot taller – exactly. When I was 16 and he was 17, notes still came in my locker, but sometimes they were in a pocket, on my lunchroom tray, or even tucked in a book: Marry me, Sara – how happy we will be.” When I was 17 and he was 18, he left. I begged him not to go – I didn’t believe in war. He wasn’t sure he believed in it either, but he said it was the right thing to do. He promised to send me lots of notes. When I was 18 and he was 19, there were no more notes.

From the Memoir Class Winter/Spring 2024

The Da Da Ching Truck

by Jeanne Medeiros

“The New Bedfords are coming! The New Bedfords are coming” It’s doubtful that Paul Revere’s warning to the Massachusetts colonists in the 1770s could have inspired more dread than these words did for myself, my brother and my sister in the 1960s. “The New Bedfords” were my father’s uncle and his wife, Tio Abilio and Tia Amelia, and whatever assorted children or friends or relatives they brought along. For us kids, first-generation, trying-to-assimilate Americans, these relations were an embarrassment of the highest order.

“The New Bedfords” spoke no English, just a loud and rapid-fire Portuguese we didn’t understand, chain-smoked, and gave us slobbery kisses. Visits to their house seemed endless and excruciatingly boring. They smoked like chimneys, yelled at each other in loud and raspy Portuguese, played endless games of cards and actually watched “Community Auditions,” a third-rate local talent show on television. We dreaded these visits. The only thing worse was when they came to our house.

Our parents moved easily between this immigrant world and the American one, and we kids probably could have done the same. But we most emphatically did not want to. We preferred our American-ness without any hyphens or duality. We learned to read with John, Jean, and Judy books we treasured even if that whitewashed suburban life bore little resemblance to our own. We were grateful that our parents had given us good solid 1950s vanilla American names – Kathy, Tom, and Jeanne. But here came “the New Bedfords” with their strange ways to expose us as the first-generation kids we were. Why, oh why, did they have to come visit us?

The Fall River we grew up in was close to 100% white, probably 95% Catholic, and fiercely ethnic. Ethnic identities were so strong that we had Portuguese churches, French churches, Irish churches, Polish churches, and Italian churches, all Catholic of course, within blocks of each other, sometimes just across the street from each other, and most people stayed where they were told they belonged. There was a hierarchy among these groups as well, with Irish being the pinnacle and Portuguese coming in last place. So we kids had learned early on that the less we identified as Portuguese, the better.

Even worse than these mortifying visits from the New Bedfords was one of the annual traditions observed by our parish, Saint Michael’s. Every year, in the early summer, our church observed a feast much beloved by Azorean communities everywhere, the feast of the Holy Ghost or Holy Spirit. It’s an elaborate feast that none of us kids ever fully understood. It commemorates the generosity that a Portuguese queen/saint showed to the poor back in the 1500s, as far as we could tell. It lasts seven weeks, has all sorts of ceremonial regalia attached to it, and culminates in a big procession and community meal that somehow acknowledges this queen’s feeding of the poor. All well and good, except for the mortifying part.

Even worse than these mortifying visits from the New Bedfords was one of the annual traditions observed by our parish, Saint Michael’s. Every year, in the early summer, our church observed a feast much beloved by Azorean communities everywhere, the feast of the Holy Ghost or Holy Spirit. It’s an elaborate feast that none of us kids ever fully understood. It commemorates the generosity that a Portuguese queen/saint showed to the poor back in the 1500s, as far as we could tell. It lasts seven weeks, has all sorts of ceremonial regalia attached to it, and culminates in a big procession and community meal that somehow acknowledges this queen’s feeding of the poor. All well and good, except for the mortifying part.

As part of this feast, the parish would distribute portions of meat and bread to parishioners who chose to participate. These apportionments or “pensoes” as they were called, were delivered to the parishioners’ homes by a big flat-bed truck carrying a brass band playing marching music. I kid you not. I look back and see these sweaty guys in tee shirts, playing tuba, trumpet, trombone, some big drum, and, worst of all, cymbals. As they drove along, it sounded like, “Da da ching! Da da ching! Da da ching ching ching! Every ”ching” was emphasized by a bang on the drum and a cymbal clang.

This truck, which we called in horror the “da da ching truck” would inch its way through our predominantly Irish neighborhood, squawking and clanging. Our neighbors had plenty of time to listen to this cacophony and wonder about the weird family whose house the truck was headed to. Then the truck would stop in front of our house with horns blaring and cymbals crashing and ceremoniously deliver the “pensao.”

This truck, which we called in horror the “da da ching truck” would inch its way through our predominantly Irish neighborhood, squawking and clanging. Our neighbors had plenty of time to listen to this cacophony and wonder about the weird family whose house the truck was headed to. Then the truck would stop in front of our house with horns blaring and cymbals crashing and ceremoniously deliver the “pensao.”

It was a nightmare. Our cover was blown. Every year, we would beg our parents, “Please don’t get the da da ching truck this year!! Please!!” And every year, they would balance their interest in being part of the feast with their silly kids’ embarrassment, just shake their heads and get it again. It would be weeks before we wanted to show our faces in the neighborhood.

I did eventually learn to appreciate and embrace my immigrant heritage, glad to see myself as something other than a “white bread” variety of American. I hope that my New Bedford relatives will accept my posthumous apologies! I also learned to push back against people who saw me as “less than” because of my ethnicity. In my late 20s, when I was looking for an apartment in Providence, a potential landlord sneered, “Medeiros, huh? So, let me ask, what do you do for a living? In my experience, most Portuguese aren’t exactly brain surgeons.” I was pretty happy to tell him that I was a housing attorney who sometimes sued people for discrimination, that I didn’t want his lousy apartment, and that, in fact, I did a little brain surgery on the side as a hobby.

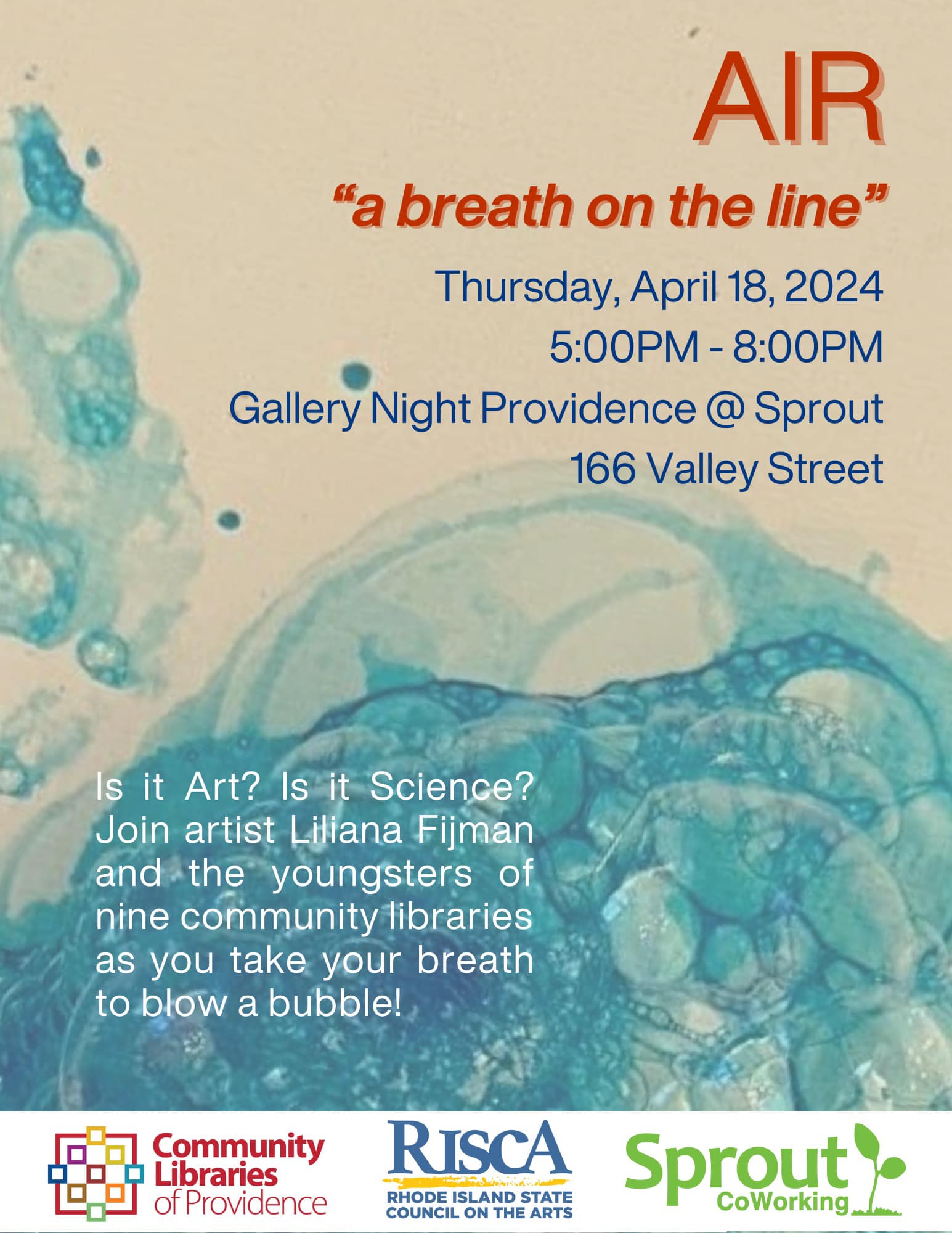

AIR: "a breath on the line"

“AIR, how to make visible what is invisible,” was my question as an artist.

Liliana Fijman, LLC member, in collaboration with the Community Libraries of Providence through the Rochambeau Library, organized an art project about AIR, called “a breath on the line”. The project was funded by RISCA, Rhode Island State Council for the Arts, and it was conducted in each one of the nine Community Libraries of Providence.

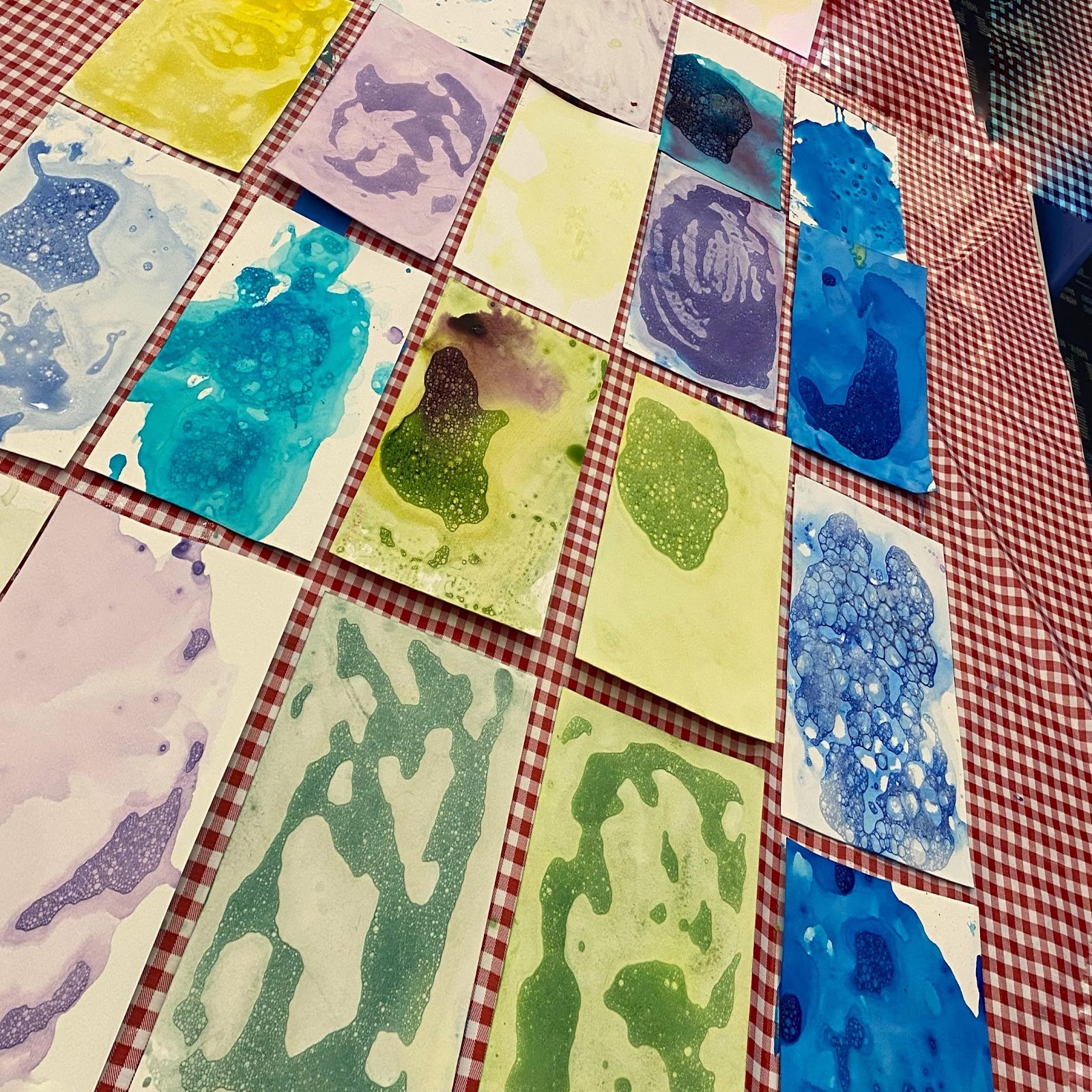

The focus of this project was double fold, bringing awareness to the basic act of healthy breathing and showing the power of creative expression through the fun act of blowing colored bubbles onto an absorbent medium of cotton paper.

Whether visiting in the morning with caretakers or by themselves after school, the budding artists, ages 3 to 7 years old, were invited to participate. Librarians complemented the work by reading books, practicing breathing in a yoga moment, or writing poetry.

As an artist herself, Liliana was most interested in giving the young artists recognition in a public place outside of their schools environs. Therefore, as a final product, all printed artwork will be seen as “folding books” to be featured in the Sprout Gallery. The show will be up from April 9 to May 3. There will be a special celebration on April 18, 2024 from 5 to 8 p.m. at the Sprout Gallery, Sprout Coworking, 166 Valley Street 6M Ste 103, Providence, RI 02909.

“It has been a most rewarding experience.” Liliana loves working with young and growing minds.

To learn more about Liliana and the a breath on the line project:

Meet Artist Liliana Fijman: www.youtube.com/watch?v=0X3NF_kCoI4

Her website: http://www.lilianafijman.com/#/

The Chatbots Are Coming

The Chatbots are coming and, like them or lump them,

You can’t pose a query or challenge to stump them.

They’re cruising the network and given free reign.

You cannot compete with your mere human brain.

Blurring the lines between real and robotic,

replacing hand drawings with graphics hypnotic,

Chatbots are adept at the art of deception;

But none was on board at an idea’s conception.

With techniques and code to mere mortals abstruse,

they draw inspiration from no human Muse.

This question is posed - it is so hard to know it:

Can Big Data capture the soul of a poet?

. . .

(Resisting a course of much lesser resistance

I wrote this myself with no AI assistance.)

Robert Kemp